x86 Nirvana Hooks & Manual Syscall Detection

January 2022

While researching an offensive capability related to syscalls and trying to decide if I wanted to publish my work. I decided that if I were to release my offensive research, I would first like to publish something that would be helpful in detecting the technique I was researching. With that goal in mind, I set out to detect manual syscalls in x86.

The Problems

Existing Published Syscall Research Overwhelmingly Focused on x64

The first problem that I ran into was there there is not a tremendous amount of recent information or examples describing x86 syscalls. The overwhelming majority of recent research has been focused on executing syscalls in x64. This makes sense in a world where 32-bit systems and applications are dwindleing. On the other hand, should we ignore their existance? Some examples recent x64 syscal research include:

I did manage to find some things that would be helpful in making syscalls from x86 but nothing as convienient at the SysWispers project for x86:

The direct-syscall repository using the Heaven’s Gate technique was the closest example of making a syscall from a 32-bit process that could be made to work somewhat like SysWhispers. (With a fair amount of work.) Primarily, it seems that the work around x86 syscalls revolves around performing manual syscalls. I did come up with something but, I’ll discuss that in a future blog post. For now, let’s stay on topic: Detecting syscalls in 32-bit processes.

How to Instrument a x86 Process

One of the first projects I ran across while looking into how to detect syscalls made from x86 processes was Jack Ullrich’s (@winternal_t) syscall-detect project. In fact, the project I am releasing with this blog is based on the syscall-detect project. I have heavily modified and changed it to improve it and make it work with 32-bit processes. He has an excellent blog post on how his tool works, that I recommend giving a read, located here. As he points out in his blog, his technique is based on Nirvana Hooks, a technique that Alex Ionescu gave a talk about in 2015 at RECON, titled: Hooking Nirvana: Stealthy Instrumentation Hooks. (talk, slides) Alex’s talk, and the majority of the examples I found, again, focused on x64 processes:

- HookingNirvana

- Hooking Via InstrumentationCallback

- Weaponizing Mapping Injection with Instrumentation Callback for stealthier process injection

- callback.c

- Windows x64 System Services Hooks and Advanced Debugging

I did find a couple of examples of performing Nirvana Hooks in x86 but, the information was limited, and I ran into some trouble putting the information I found to use.

- Windows 10 Hooking Nirvana explained

- Instrumentationcallback and advanced debugging

- instrumentation-callback-x86

What I did find was enough to lead me down the path I needed to to understand how Instrumentation Callbacks (Nirvana Hooks) work in x86. The remainder of this blog post will detail what I was able to discover and how I implemented a manual syscall detecetion tool that works in both x86 and x64.

How Instrumentation Callbacks Work in x86

There were not many good examples of how Nirvana Hooks work in x86 processes. I wanted to understand how exactly the Instrumentation Callback routine was called and what values were stored where when the Instrumentation Callbak is made. I started by doing more searches to see what information I could find. The information in the Wolf’s IT Thoughts blog post titled Winodws 10 Hooking Nirvana explained (archive.org) contained a lot of good information that got me pointed in the right direction. The “assumed” assessment of what the Wow64SetupForInstrumentationReturn function does in Wolf’s blog is pretty accurate but was too high-level for me. I wanted to understand what wa going on in more detail. With that goal, I fired up IDA, Cutter, and WinDbg and got going.

In the following sections I am going to describe the basic sequence of events that leads to code execution being redirected to a Nirvana Hook instrumentation Callback. I will then dig deeper into several elements to help the reader gain a better understanding of what is taking place in the background when Nirvana Hooks are enabled. Finally, I will describe and provide code that will demonstrate functioning Nirvana Hooks in an x86 process.

Path to Nirvana

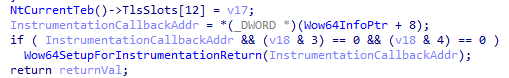

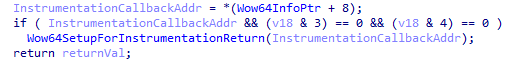

The road to executing a Nirvana Hook’s InstrumentationCallback routine starts in the Wow64SystemServiceEx function. In a Wow64 process this function is responsible for resolving and triggering syscalls. At the end of this function, the third element (What I’m calling the InstrumentationCallbackAddr) of the Wow64Info structure is checked and if it exists, the Wow64SetupForInstrumentionReturn function is called and the value of the third element is passed as an argument.

Figure 01: Wow64SetupForInstrumentationReturn Function Call

What is Wow64Info?

Another myserious structure I knew nothing about was the WOW64INFO structure. Before discussing how Wow64SetupForInstrumentationReturn works, first I discuss this new structuer to help better understand what it is and what information it contains. Others have reversed this structure. 16 19 20 The existing work was extremely helpful but I wished to understand this structure better. Also, something about the previous reversing didn’t add up with what I observed while reversing wow64.dll. After spending many hours reversing functions in wow64.dll and wow64cpu.dll I came to understand the structure better and what I came up with was just slightly different than what others had come up with before. It’s possible that it has been restructured at some point? The following is how I understand the structure is formatted now:

typedef struct _WOW64INFO {

DWORD PageSize;

DWORD CpuFlags;

DWORD InstrumentationCallback;

DWORD Unknown1;

DWORD Unknown2;

WORD NativeCpuArch;

WORD EmulatedCpuArch;

} WOW64INFO, *PWOW64INFO;Code 01: Reversed Wow64Info Structure.

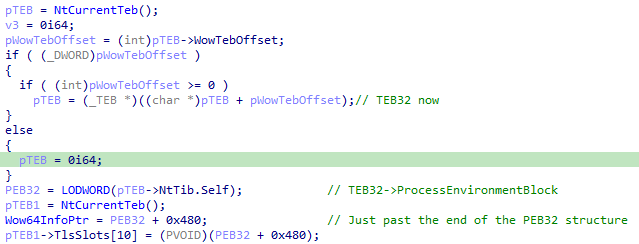

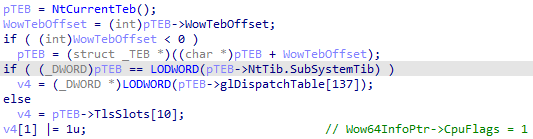

This structure is stored in two locations. The first location is just past the 32-bit PEB structure and in 64-bit Thread Local Storage slot 10 (e.g. TEB.TlsSlot[10]). After reversing it and cleaning it up a bit, the follwoing code is responsible for storing the location of the WOW64INFO structure. It is part of the Wow64LdrpInitializer function located in wow64.dll.

Figure 02: Code that Sets Wow64InfoPointer

As you can see from my comments, the pTEB pointer is reused and changed from the 64-Bit TEB to the 32-bit TEB. This means that instead of pointing to TEB->NtTib.Self, it instead points to TEB->ProcessEnvironmentBlock. 0x480 happens to the the size of the PEB structure in a 32-bit process, as demonstrated in the following truncated WinDbg output.

0:000> dt ntdll!_PEB

+0x000 InheritedAddressSpace : UChar

+0x001 ReadImageFileExecOptions : UChar

+0x002 BeingDebugged : UChar

...

+0x474 SixtySecondEnabled : Pos 0, 1 Bit

+0x474 Reserved : Pos 1, 31 Bits

+0x478 NtGlobalFlag2 : Uint4B

0:000> ?? sizeof(_PEB)

unsigned int 0x480Code 02: Truncated dump of the PEB32 structure in WinDbg demonstrating the structures size.

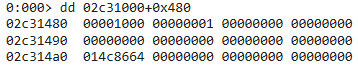

Going a step further, it is possible to dump the memory at this location to view the values stored in the stucture. In the following screenshot, the value 0x02c31000 is the address of the PEB structure in a 32-bit process:

Figure 03: Dump of Wow64Info Structure at PEB32+0x480

Next, let’s fill in the values for the elements of the WOW64INFO structure:

| Element | Value |

|---|---|

| PageSize | 0x00001000 (4096) |

| CpuFlags | 0x00000001 |

| InstrumentationCallbackAddr | 0x00000000 |

| Unknown1 | 0x00000000 |

| Unknown2 | 0x00000000 |

| NativeCpuArch | 0x8664 (IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_AMD64 21) |

| EmulatedCpuArch | 0x014C (IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386 21) |

Table 01: Wow64Info Initial Values

WOW64INFO Structure Value Initialization

The next task was to determine how each of the elements stored in the WOW64INFO structure are initialized. The first element, PageSize is initialezed in the wow64!ProcessInt function. The following reversed code sets the value to 0x1000 (4096), the size of a memory page:

Figure 04: Wow64Info->PageSize Set to 4096 Bytes

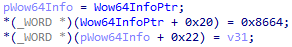

We will skip down to the last two elements, NativeCpuArch and EmulatedCpuArch and come back to CpuFlags last. Both NativeCpuArch and EmulatedCpuArch are initialized in the ntdll!Wow64LdrpInitialize function. NativeCpuArch is initialized to equal 0x8664 which equates the IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_AMD64 21 and EmulatedCpuArch is initialized to 0x014C which equates to IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386 21. The following code is responsible for the assignments. The variable v31 contains 0x014C:

Figure 05: Wow64Info->NativeCpuArch & Wow64Info->EmulatedCpuArch Values Populated

Finally, the CpuFlags element. This was a bit more difficult to track down becaue it is actually initalized from an entirely different DLL. This value seems to be initialized using the wow64cpu!BTCpuProcessInit function. The following code seems to be responsible, if anyone knows of another location please contact me:

Figure 05: Wow64Info->CpuFlags set to 0x00000001

How Windows Checks if Callbacks are Enabled?

Now, armed with a little bit of information about the WOW64INFO structure, lets take a look at what happens in the wow64!Wow64SystemServiceEx function. This function, as previously stated, resolves and initiates a call that will wind up sending the CPU from x86 to x64 bit mode to execute a syscall. The interesting part of Wow64SystemServiceEx is towards the end of the function. The specific instructions are displayed in Figure 06:

Figure 06: Checking for and Initiating the Nirvana Hook Instrumentation Callback

The value of WOW64INFO->InstrumentationCallbackAddr (What I’m calling it anyway…) is checked. If it exists, it is passed to the wow64!Wow64SetupForInstrumentationReturn function as an argument. This value is later used to redirect execution. This means that the address of our Nirvana Hook callback is stored in the WOW64INFO structure that lives just beyond the PEB structure of a 32-bit process.

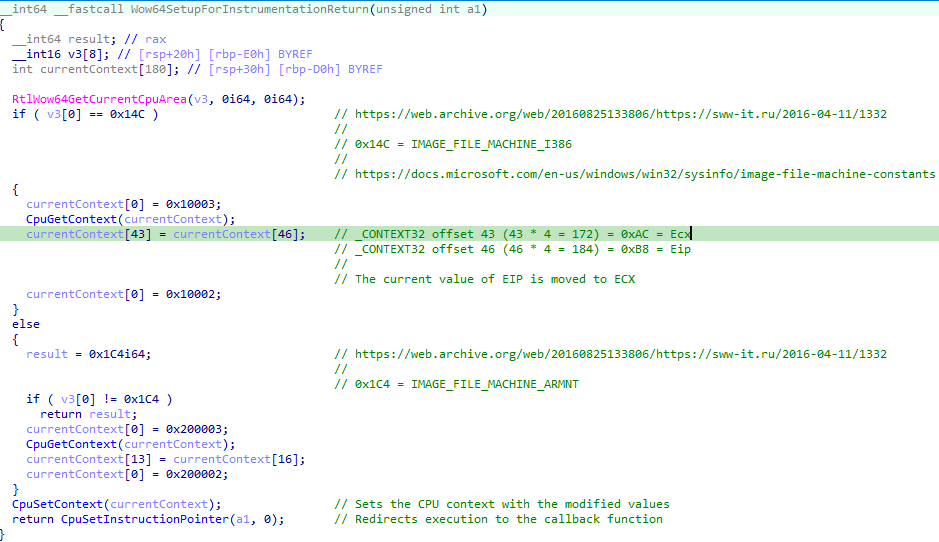

Instrumentation Callback Setup

Now that we know how the Instrumentation Callback function address is obtained, lets take a look at the wow64!Wow64SetupForInstrumentationReturn function. The following steps describe what this function does:

-

Gets the current CpuArea and stores it.

-

The first element of the stored CpuArea is checked to see if it equals 0x014C (IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386 21).

-

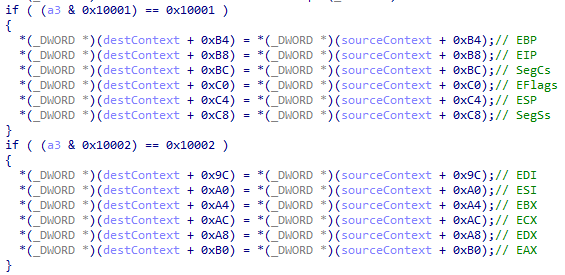

If the previous condition is true, the CONTEXT->ContextFlags value is set to 0x10003 in an empty CONTEXT variable. A ContextFlags value of 0x10003 coppies the following registers:

- EBP, EIP, SegCs, EFlags, ESP, SegSs, EDI, ESI, EBX, ECX, EDX, EAX

-

The same CONTEXT variable is passed to the CpuGetContext function where the requested values are populated.

-

The value from CONTEXT->EIP is stored in CONTEXT->ECX. This means that the address our instrumentation will need to return execution will be accessible to our Instrumentation Callback code in the ECX register.

-

CONTEXT->ContextFlags is set to 0x10002. A ContextFlags setting of 0x10002 only sets EDI, ESI, EBX, ECX, EDX, and EAX.

-

CpuSetContext is called to update the CPU context. The relevent code resposible for copying the registers can be found in the ntdll!RtlpCopyLegacyContextX86 function.

Figure 07: Code in ntdll!RtlpCopyLegacyContextX86 Function Responsible for Copying Registers

- CpuSetInstructionPointer is called to redirect execution to a1, which is the address obtained from the WOW64INFO structure and passed to Wow64SetupForInstrumentationReturn from the Wow64SystemServiceEx function.

SIDE NOTE: This function (and many other functions in wow64.dll)

seems to contain code meant to handle the ARM CPU architecture.The Figure 08 is a screen capture of the cleaned up code responsible for the process described in the previous list, along with the notes from my attempt to reverse engineer it.

Figure 08: Wow64SetupForInstrumentationReturn with Notes

Setup Summary

We now understand where the callback address is stored, how the CPU context is manipulated, and code execution is redirected to our Nirvan Hook Callback. The only thing that remains, is to write a callback that will:

- Preserve the registers, including the saved EIP address that is now stored in the ECX register.

- Preserve the CPU Flags

- Perform whatever processing we require. Without triggering any new syscalls before setting a flag to disable instrumentation first.

- Restore the CPU Flags

- Restore the CPU Registers

- Redirect execution back to the oritginal EIP address that is stored in the ECX register.

Using Nirvana Hooks

In this section, I will detail the modifications I made to Jack Ullrich’s Syscall-Detect 8 project to use Nirvana Hooks to detect manual syscalls made from User space instead of Kernel space. It was the first project I found when looking into detecting manual syscalls and what served to send me down the rabbit hole that resulted in the research I performed for this blog post. I was attracted by his use of RtlCaptureContext and RtlRestoreContext to capture and restore the CPU context. It is an awesome project, only one problem… I was dealing with a 32-bit application but could only find 64-bit solutions. On top of that, RtlCaptureContext and RtlRestoreContext are not available in 32-bit processes.

Project Architecture and Target Changes

I have made the following changes to the Platform Target and Configuration Type changes:

- I have written my version of the instrumentation to support both x86 and x64 CPUs

- It is also capable of being compiled as a DLL so that it can be loaded into another process as Jack Ullrich demonstrated or as a EXE that can be run for demonstration and testing purposes.

Logging Changes

To facilitate logging in an application that does not, or cannot use a console, I changed the logging facility from the console to use DebugView. 23

x86 Specific Changes

Working top to bottom in the source, I will point out notable changes I needed to make to support x86. One thing that I will not discuss in detail but is worth pointing out is the pointer type changes. The types I selected were specifically chosen to support both 32-bit and 64-bit pointers depending on the project’s target CPU architecture.

New Sanity Checks

RIP does not exist in 32-bit mode. To support this, I changed the RIP_SANITY_CHECK and changed the argument names to be more architecture agnostic.

#define IP_SANITY_CHECK(ip,BaseAddress,ModuleSize) (ip > BaseAddress) && (ip < (BaseAddress + ModuleSize))

...

#ifdef _WIN64

sanityCheckNt = IP_SANITY_CHECK(ctx->Rip, NtdllBase, NtdllSize);

sanityCheckWu = IP_SANITY_CHECK(ctx->Rip, W32UBase, W32USize);

#else

sanityCheckNt = IP_SANITY_CHECK(ReturnAddress, NtdllBase, NtdllSize);

sanityCheckWu = IP_SANITY_CHECK(ReturnAddress, W32UBase, W32USize);

#endifCode 03: Changes to the sanity check macro to make it more architecture agnostic.

New InstrumentationCallback Function Deleration

Because RtlCaptureContext and RtlRestoreContext are not supported in 32-bit processes, I had to modify the InstrumentationCallback function declaration so that it would be different based on the CPU architecutre the project is compiled for.

#ifdef _WIN64

extern "C" void InstrumentationCallback(PCONTEXT, uintptr_t, uintptr_t);

#else

extern "C" void InstrumentationCallback(uintptr_t, uintptr_t);

#endif

...

void InstrumentationCallback(

#ifdef _WIN64

PCONTEXT ctx,

#endif

uintptr_t ReturnAddress,

uintptr_t ReturnVal

) {

...

}Code 04: Architecture specific InstrumentationCallback function declaration.

Restoring Registers

Again, due to the RtlCaptureContext and RtlRestoreContext, the registers are being stored and restored completely in the Asembly code. This means that the variables being set in the next section are completly for show when running in 32-bit mode. I also chose to restore all of the registers so that they would be set exactly as they where when the Nirvana Hook was triggered.

#ifdef _WIN64

cbDisableOffset = 0x02EC; // TEB64->InstrumentationCallbackDisabled offset

instPrevPcOffset = 0x02D8; // TEB64->InstrumentationCallbackPreviousPc offset

instPrevSpOffset = 0x02E0; // TEB64->InstrumentationCallbackPreviousSp offset

ctx->Rip = *((uintptr_t*)(pTEB + instPrevPcOffset));

ctx->Rsp = *((uintptr_t*)(pTEB + instPrevSpOffset));

ctx->Rcx = ctx->R10;

ctx->R10 = ctx->Rip;

#else

//PTEB32 pTEB = (PTEB32)NtCurrentTeb();

cbDisableOffset = 0x01B8; // TEB32->InstrumentationCallbackDisabled offset

instPrevPcOffset = 0x01B0; // TEB32->InstrumentationCallbackPreviousPc offset

instPrevSpOffset = 0x01B4; // TEB32->InstrumentationCallbackPreviousSp offset

#endifCode 05: Restoring register values from saved locations in the TEB.

New SetInstrumentationCallbackHook Function

To support 32-bit and 64-bit, I borrowed and modified a portion of function that ScyllaHide 22 uses to set the Instrumentation Callback hook.

// Code inspired by ScyllaHide - https://github.com/x64dbg/ScyllaHide/blob/master/HookLibrary/HookHelper.cpp

NTSTATUS SetInstrumentationCallbackHook(HANDLE ProcessHandle, BOOL Enable)

{

CallbackFn Callback = Enable ? InstrumentationCallbackProxy : NULL;

// Windows 10

PROCESS_INSTRUMENTATION_CALLBACK_INFORMATION CallbackInfo;

#ifdef _WIN64

CallbackInfo.Version = 0;

#else

// Native x86 instrumentation callbacks don't work correctly

BOOL Wow64Process = FALSE;

if (!IsWow64Process(ProcessHandle, &Wow64Process) || !Wow64Process)

{

//Info.Version = 1; // Value to use if they did

return STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED;

}

// WOW64: set the callback pointer in the version field

CallbackInfo.Version = (ULONG)Callback;

#endif

CallbackInfo.Reserved = 0;

CallbackInfo.Callback = Callback;

return NtSetInformationProcess(ProcessHandle, ProcessInstrumentationCallback,

&CallbackInfo, sizeof(CallbackInfo));

}Code 06: New SetInstrumentationCallbackHook function to handle both x86 and x64 processes.

The Assembly

Because I verified that the value of EIP was being stored in the ECX register prior to the Instrumentation Callback being made. The task of writing some Assembly to store the current of the registers and restore them before returning execution back to it’s normal flow was fairly simple. I also added a check of the InstrumentationCallbackDisabled flag to resume execution without calling the InstrumentationCallback function if a syscall is already being instrumented. This is the code that I ended up with:

include ksamd64.inc

include CallConv.inc

.686

.model flat

public _InstrumentationCallbackProxy

assume fs:nothing

extern _InstrumentationCallback:PROC

.code

_InstrumentationCallbackProxy PROC

push esp ; back-up ESP, ECX, and EAX to restore them

push ecx

push eax

mov eax, 1 ; Set EAX to 1 for comparison

cmp fs:1b8h, eax ; See if the recurion flag has been set

je resume ; Jump and restore the registers if it has and resume

pop eax

pop ecx

pop esp

mov fs:1b0h, ecx ; InstrumentationCallbackPreviousPc

mov fs:1b4h, esp ; InstrumentationCallbackPreviousSp

pushad ; Push registers to stack

pushfd ; Push flags to the stack

cld ; Clear direction flag

push eax ; Return value

push ecx ; Return address

call _InstrumentationCallback

add esp, 08h ; Correct stack postion

popfd ; Restore stored flags

popad ; Restore stored registers

mov esp, fs:1b4h ; Restore ESP

mov ecx, fs:1b0h ; Restore ECX

jmp ecx ; Resume execution

resume:

pop eax

pop ecx

pop esp

jmp ecx

_InstrumentationCallbackProxy ENDP

assume fs:error

endCode 07: x86 Assembly InstrumentationCallbackProxy

x64 Specific Changes

Not much of the core functionality was changed for the x64 version of the code from the original. The main functional differences are in the Assembly language used in the callback. Most notably:

- I added a routine to check the InstrumentationCallbackDisabled flag and resume execution if a syscall is already being instrumented.

- I fixed the call to RtlCaptureContext to include shadow space on the stack before making the call.

- Since I modified the InstrumentationCallback function, I needed to provide the additional arguments in the RDX and R8 registers.

include ksamd64.inc

include CallConv.inc

extern InstrumentationCallback:proc

EXTERNDEF __imp_RtlCaptureContext:QWORD

.code

InstrumentationCallbackProxy proc

push rsp ; Back-up RSP, R10, and RAX to preserve them

push r10

push rax

mov rax, 1 ; Set RAX to 1 for comparison

cmp gs:[2ech], rax ; See if the recursion flag has been set

je resume ; Jump and restore the registers if it has and resume

pop rax

pop r10

pop rsp

mov gs:[2e0h], rsp ; Win10 TEB InstrumentationCallbackPreviousSp

mov gs:[2d8h], r10 ; Win10 TEB InstrumentationCallbackPreviousPc

mov r10, rcx ; Save original RCX

sub rsp, 4d0h ; Alloc stack space for CONTEXT structure

and rsp, -10h ; RSP must be 16 byte aligned before calls

mov rcx, rsp

mov rdx, 0h

sub rsp, 20h

call __imp_RtlCaptureContext ; Save the current register state. RtlCaptureContext does not require shadow space

mov r8, [rcx+78h] ; The value of RAX from the CONTEXT object stored at RSP

mov rdx, gs:[2d8h] ; The saved RIP address

sub rsp, 20h

call InstrumentationCallback ; Call main instrumentation routine

resume:

pop rax

pop r10

pop rsp

jmp r10

InstrumentationCallbackProxy endp

endCode 08: x64 Assembly InstrumentationCallbackProxy

Code

I am releasing the code I wrote for this research on GitHub. You can view the project here:

Demonstration

The following video demonstrates the DLL version of the project being loaded into a project that makes a manual syscall to demonstrate the ability of the tool to detect a manual syscall in x86.

Figure 08: Demo of inst-callback loaded into another project.

Sources

- https://outflank.nl/blog/2019/06/19/red-team-tactics-combining-direct-system-calls-and-srdi-to-bypass-av-edr/

- https://github.com/jthuraisamy/SysWhispers

- https://github.com/vxunderground/VXUG-Papers/tree/main/Hells%20Gate

- https://github.com/j00ru/windows-syscalls

- https://gist.github.com/wbenny/b08ef73b35782a1f57069dff2327ee4d

- https://github.com/nothydud/direct-syscall

- https://raw.githubusercontent.com/darkspik3/Valhalla-ezines/master/Valhalla%20%231/articles/HEAVEN.TXT

- https://github.com/jackullrich/syscall-detect

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pHyWyH804xE

- https://github.com/ionescu007/HookingNirvana/blob/master/Esoteric%20Hooks.pdf

- https://github.com/ionescu007/HookingNirvana

- https://secrary.com/Random/InstrumentationCallback/

- https://splintercod3.blogspot.com/p/weaponizing-mapping-injection-with.html

- https://gist.github.com/esoterix/df38008568c50d4f83123e3a90b62ebb

- https://www.codeproject.com/Articles/543542/Windows-x64-system-service-hooks-and-advanced-debu

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160825133806/https://sww-it.ru/2016-04-11/1332

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160517025353/http://everdox.blogspot.ru/2013/02/instrumentationcallback-and-advanced.html

- https://github.com/ec-d/instrumentation-callback-x86

- https://wbenny.github.io/2018/11/04/wow64-internals.html

- http://blog.rewolf.pl/blog/?p=621

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/sysinfo/image-file-machine-constants

- https://github.com/x64dbg/ScyllaHide

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/downloads/debugview